05/02/2012

Vient de paraître...

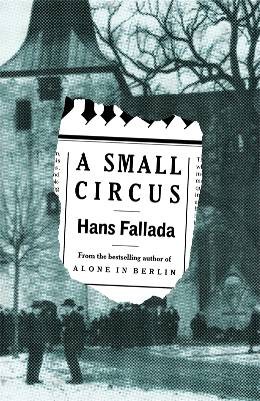

Le roman de Hans Fallada, Bauern, Bonzen und Bomben (1931), vient d'être traduit en anglais et est paru en ce début février sous le titre de "A small Circus". Ce titre fait allusion à l'avant-propos du roman qui s'intitule "Un petit cirque appellé Monte". Selon les biographes, ce titre devait être à l'origine celui du roman.

En France, une traduction est parue, en 1942, chez Fernand Sorlot, sous le titre de Levée de fourches, traduit par Edith Vincent. Mais cet ouvrage est difficilement trouvable aujourd'hui. Espérons que, suivant l'exemple anglais, l'ouvrage sera si possible traduit à nouveau, à partir du texte intégral et enfin republié.

Ce livre retrace un épisode de la révolte paysanne dans le Schleswig-Holstein en 1929, à Neumünster (Althom dans le roman), plus précisément. Episode que Rudolf Ditzen suivra de près pour le compte du journal local, le General-Anzeiger für Neumünster (Die Chronik, dans le roman). C'est d'ailleurs sous les traits du journaliste Tredup que Rudolf Ditzen apparaît.

Nous publions, en notes séparées, des recensions parues en anglais sur ce livre.

La rédaction

17:30 Publié dans Actualité, Bibliographie, Textes de Hans Fallada | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0)