23/03/2013

Histoires de récidive

LITTÉRATURE

Prison et littérature : « Deux histoires de récidive : Hans Fallada et Alfred Döblin »

Le sociologue et chercheur Claudio Besozzi travaille à une thèse consacrée à l’image de la prison dans la littérature. Il nous livre régulièrement des textes présentant les écrivains de langue française, allemande ou italienne qui ont parlé de la prison, voire fait l’expérience de la privation de liberté, et montré comment la détention peut être vécue de façon très différente selon la personnalité du détenu.

Deux histoires de récidive : Hans Fallada et Alfred Döblin [1]

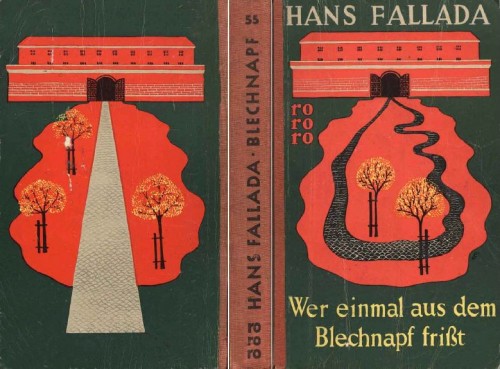

Pour des raisons qui nous échappent, le thème de la prison, omniprésent chez les écrivains européens du xixe siècle, n’a pas ou peu laissé de trace dans la littérature allemande de l’époque. Ce n’est qu’au début du xxe siècle que des auteurs allemands s’approchent de la prison et en font un sujet littéraire. Pendant la période entre les deux guerres mondiales, marquée par les bouleversements politiques allant de la proclamation de la république jusqu’à l’avènement du national-socialisme, deux romans sont publiés à quelques années de distance : « Wer aus dem Blechnapf frisst » de Hans Fallada et « Berlin Alexanderplatz » de Alfred Döblin. Le premier autobiographique, le deuxième, œuvre de fiction, ces écrits nous proposent une réflexion à la fois sur une société à la dérive et sur le désarroi des individus qui essaient tant bien que mal d’y trouver une place. Dans un tel contexte, la prison représente un élément incontournable : comme étape ultime et inévitable de la déchéance, mais aussi comme un palliatif à la misère du quotidien. Elle est le symbole à la fois de l’échec de l’individu et d’un ordre que la société n’est plus à même d’offrir aux citoyens. Mais les considérations de Fallada et de Döblin ne s’arrêtent pas là. En abordant le problème de la récidive, ils anticipent les critiques de l’institution carcérale qui, à partir des années soixante, mettront en cause sa fonction résocialisatrice. Si les détenus dont ces écrivains font le portrait se sentent « chez eux » en prison, c’est que celle-ci n’a pas de sens. S’ils considèrent que la véritable punition intervient au moment où ils quittent leur cellule pour réintégrer la vie en liberté, cela signifie que la prison et la société ont failli à la tâche qu’ils se sont donnée : au lieu de produire des hommes « meilleurs », l’une et l’autre entretiennent leurs faiblesses.

Ceci dit, la reconnaissance du fait qu’il y a du sable dans l’engrenage de la punition ne va pas de pair, chez Fallada et Döblin, avec une déresponsabilisation de l’individu. Les protagonistes des deux romans, dont il est question ici – Franz Biberkopf et Willi Kufalt – sont les victimes de leur bêtise. Ils se laissent pousser par la vie, au lieu de la dominer. Ils [i]rêvent d’une existence sans soucis ni tracas et recourent à l’alcool lorsque la réalité les ramène sur terre. N’importe quel comportement, si anodin soit-il, se transforme chez eux en véritable catastrophe, même lorsqu’il est posé avec les meilleures intentions. Ils invoquent la malchance, mais ils trébuchent sur des obstacles qu’ils ont eux-mêmes placés sur le chemin. Bien entendu, la société ne leur fait pas de cadeaux et contribue à façonner une carrière qui aboutit, avec une logique inexorable, au retour en prison. Mais les personnages de Fallada et de Döblin, chacun à sa manière, se conforment mollement au destin écrit par la société comme on s’abandonne au courant d’une rivière, sans prêter attention aux branches auxquelles ils pourraient s’agripper.

1. Hans Fallada : le mythe de l’éternel retour

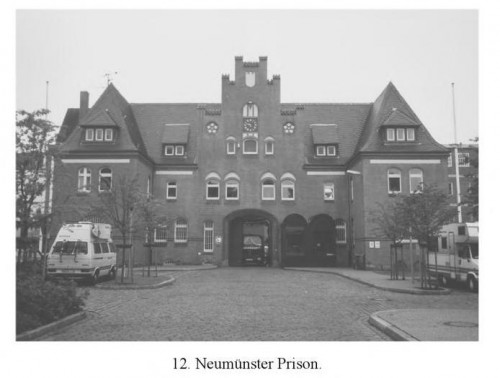

Une vie peu banale, celle de Rudolf Dietzen, alias Hans Fallada (1893 – 1947). Issu d’une famille aisée (le père est magistrat), il fréquente l’école tout d’abord à Berlin, puis à Leipzig. Son adolescence est caractérisée par un rapport conflictuel avec le père, qui l’envoie dans un internat lorsqu’il découvre que Rudolf a écrit une lettre d’amour à une fille : un épisode que l’écrivain reprendra dans le roman « Wer einmal aus dem Blechnapf frisst » en guise d’explication aux déboires du protagoniste[ii]. En 1911 Rudolf Dietzen et son ami Hanns Dietrich von Necker décident de se suicider, en déguisant leur acte en duel. L’ami succombe aux blessures ; Rudolf, qui s’en échappe de justesse, est tout d’abord accusé d’homicide, puis interné dans une clinique psychiatrique à Tannenfeld. Il a 19 ans. C’est probablement au cours de cet internement qu’il développe une dépendance à la morphine. À sa sortie, il abandonne les études, accomplit un apprentissage d’agriculteur et s’engage dans une carrière d’agronome. Mais Rudolf préfère la littérature au travail des champs. Son premier roman, écrit sous le pseudonyme de Hans Fallada, paraît en 1919. Dans les années qui suivent, il subit plusieurs cures de désintoxication. La dépendance à l’alcool et autres drogues sont aussi à l’origine de ses déboires avec la justice. Hans Fallada est condamné une première fois à 6 mois de prison pour détournement de fonds en 1923, peine qu’il purge à la prison de Greifswald. Il subira une deuxième condamnation deux ans après pour les mêmes raisons. Cette fois la peine est plus lourde : deux ans et demi à la prison centrale de Neumünster. Comme le héros de son roman, il travaille à la sortie dans des bureaux de dactylographie et comme démarcheur de publicité.

Ces déconvenues n’empêchent pas Fallada de poursuivre son activité d’écrivain. Engagé par Rowohlt dans sa maison d’édition, Fallada publie en 1932 « Kleiner Mann, was nun ? »[iii], roman qui lui vaudra une renommée internationale. Après la prise de pouvoir par les nationale-socialistes, Fallada est déclaré « auteur non désiré », décision qui sera levée quelques mois plus tard. Mais ses rapports avec le pouvoir restent tendus. Sur dénonciation du propriétaire de la maison qu’il vient d’acheter, il est détenu pendant deux semaines pour activités subversives. Son roman « Wer einmal aus dem Blechnapf frisst »[iv], dont il sera question plus tard, est interdit par les autorités. Malgré cela, Fallada ne peut pas se décider à émigrer, comme tant d’autres écrivains, et s’arrange tant bien que mal avec l’idéologie dominante, quitte à se faire taxer de collaborateur.[v]

En 1944, Hans Fallada est de nouveau interné à la clinique de Neustrelitz – en réalité une prison abritant des criminels souffrant d’une maladie mentale – pour avoir menacé sa femme, dont il venait de se séparer, avec un pistolet. Un an plus tard, nouveau séjour dans une clinique pour une cure de désintoxication. À la fin de la guerre, il sera à Berlin, où il rédige son roman le plus connu, « Jeder stirbt für sich allein »[vi]. Hans Fallada meurt en 1947 des suites d’un accident cardiovasculaire.

Un paradigme de la récidive

Publié une année après la prise de pouvoir par Hitler, en 1934, « Wer einmal aus dem Blechnapf frisst » est un roman autobiographique, le protagoniste, Willy Kufalt, étant à bien des égards un sosie de l’auteur. Condamné à cinq ans de prison pour détournement de fonds, Willy Kufalt se prépare à sa mise en liberté. Après quelques hésitations, il accepte de commencer sa nouvelle vie à Hambourg, dans une maison de transition lui offrant gîte et travail. Toutefois le sentiment d’être exploité et des règlements vexatoires lui font changer d’idée. Avec des camarades, il décide de se mettre à son compte et d’ouvrir un petit atelier de dactylographie. En un premier temps, le succès est au rendez-vous. Willy décroche un contrat, bien que de façon un peu cavalière, réussit à trouver les machines à écrire et le bureau. Les premières livraisons lui apportent quelques sous, mais les choses se gâtent par la suite. Accusé d’avoir acheté les machines à écrire frauduleusement, Willi est incarcéré jusqu’à ce qu’il puisse prouver sa bonne foi.

De nouveau en liberté, mais sans le sou, il essaye désespérément de joindre les deux bouts tout en restant dans la légalité. Peine perdue. La rencontre avec un camarade de détention qui lui fait miroiter l’opportunité de gagner de l’argent « facile » ébranle sa détermination. Willi se laisse entraîner, un peu malgré lui, dans un vol à la tire, utilise sa partie du butin pour quitter Hambourg et s’établir dans une petite ville : la même petite ville dans laquelle il a vécu cinq ans derrière les barreaux. Un semblant de normalité s’installe : il trouve du travail comme démarcheur de publicité, gagne assez d’argent pour se permettre une chambre confortable, rencontre une fille qu’il se propose de marier. Mais le passé le rattrape aussitôt : soupçonné injustement d’avoir volé de l’argent à une vieille dame, il retourne à Hambourg, bien décidé à tourner le dos à une société qui ne veut pas de lui. Willi Kufalt change de nom, renoue ses liens avec le monde interlope, rêve du grand coup qui le mettrait à l’abri des soucis quotidiens.

Ayant découvert une faille dans la surveillance d’une bijouterie, dont les vitrines promettent un butin substantiel, Willi demande de l’aide à un ex-camarade de prison avant de commettre un cambriolage qui est au-dessus de ses moyens. Batzke, le complice, se montre tout d’abord réticent, laissant Willi Kufalt aux prises avec ses rêves et la conscience de sa médiocrité. Exclu par la société, il se voit également repoussé par ceux qui la défient. Dans un acte désespéré, dernière tentative de prouver à lui-même et aux autres ce de quoi il est capable, il attaque une femme, lui envoie un coup de poing au visage et lui vole son sac à main. Le sentiment de supériorité que lui procure l’exercice de la violence, conduiront Willi à commettre une série d’actes semblables, jusqu’à ce que la police l’arrête. Le retour en prison, dans « sa » cellule, ressemble paradoxalement à un « happy end ».

L’histoire de Willi Kufalt, telle que racontée par Hans Fallada, représente un paradigme de la récidive, un schéma explicatif qui a donné forme aux discours sur la prison jusqu’à nos jours. Tous les ingrédients y sont réunis : les effets pervers de l’enfermement, la fermeture de la société vis-à-vis des personnes qui sortent de prison, les difficultés qui s’opposent à une réinsertion sociale, le rôle des « mauvaises fréquentations », et j’en passe. Dans cet ordre d’idées, la récidive apparaît non comme le résultat d’une équation personnelle, mais d’une logique sociale qui échappe au contrôle des individus. Willi Kufalt sort de prison avec les meilleures intentions, il faut ce qu’il faut pour rester dans la légalité, rêve d’une vie paisible, de travail et de famille. Ses efforts se brisent toutefois contre les obstacles que le système dresse sur son chemin.

Une lecture plus attentive de l’œuvre de Fallada nous permet néanmoins d’aller au-delà d’un tel paradigme et de découvrir, grâce à la description minutieuse que l’auteur nous fournit, des aspects de ce processus qui ouvrent la porte à une représentation plus différenciée et plus réfléchie de ce qui se présente à premier abord comme une logique implacable.

Attendre la sortie

L’action débute deux jours avant la date de la sortie : une courte période de temps, qui s’étire dans le roman jusqu’à la page 110. Deux jours avant sa libération, Willi Kufalt est encore absorbé par le quotidien de la prison : nettoyer la cellule, vider le seau, se procurer du tabac, rencontrer tel ou tel camarade. On dirait que l’ensemble de sa routine, intériorisée pendant cinq longues années, n’ont qu’une seule fonction : lui faire oublier l’échéance qui l’attend. Ce n’est que dans le calme relatif du soir que ses pensées s’arrêtent sur ce que sera la vie de l’autre côté des barrières :

« Si au moins je savais quoi faire, quand je sors d’ici ! Si je n’ai pas de travail, ils vont m’envoyer mon pécule à l’assistance sociale et je ne pourrai aller chercher que quelques sous par semaine… Ils se foutent le doigt dans l’œil ! Je préfère faire un coup tordu… » (p. 10).

Pour le moment, rien n’est définitif, le scénario n’a pas encore été écrit. Travailleur ou truand : le choix est entre ses mains. Un premier obstacle toutefois : des règlements qui veulent aider – empêcher les ex-détenus de flamber leurs économies en quelques jours – et qui n’aident pas. Se contenter de l’argent dispensé par l’assistance sociale signifierait renoncer à ce dont Willi a été privé pendant cinq ans. À quoi bon la liberté, s’il faut se contenter de travailler, dormir et manger ? Mais tout ceci n’est, pour le moment, qu’une tentative de dépasser l’insécurité qui l’habite, en s’accrochant à l’idée qu’il est assez malin pour se tirer d’affaire dans n’importe quelle situation. Si le système lui pose des colles, il saura les éviter. Figées dans le court terme, ses pensées ne peuvent aller plus loin que l’alternative entre la légalité et l’illégalité :

« Peut-être je fais un mauvais coup, peut-être je vais travailler au bureau de mon beau-frère » (p. 19).

En réalité, les deux options sont tout aussi en dehors de la réalité l’une que l’autre. Willi Kufalt n’est pas un truand et son beau-frère (comme le reste de sa famille) ne veut plus rien savoir de lui. Il faudra trouver autre chose, mais quoi ? L’insécurité reprend le dessus, les questions se multiplient et restent sans réponse. Louer une chambre, trouver du travail, et « l’argent qui file entre les doigts » (p. 22) : plus il y pense, plus de tels problèmes deviennent – dans son imagination et avant même de les avoir rencontrés – des obstacles insurmontables. Et face à ce qui l’attend dehors, Willi ne peut s’empêcher de jeter un regard nostalgique sur les années passées dans cette prison qu’il devra quitter bientôt :

« Il était bien ici, il s’y est vite adapté… Somme toute, il a eu du bon temps, la sortie venait trop vite, rien n’était prêt, il resterait volontiers encore quelques semaines… » (p. 23).

Les pensées se bousculent, peur et espoir s’alternent, s’entrechoquent, l’une chasse l’autre. Les projets, à peine formulés, éclatent comme des bulles de savon : clichés d’une petite vie bourgeoise bien tranquille, hors de sa portée. Bien sûr, il sait ce qu’il faudrait faire une fois dehors, mais la façon dont ces banalités sont formulées dans la tête ressemble étrangement à une prière :

« Le mieux, ce serait un revenu régulier, sûr, même un petit revenu. Ne rien avoir à faire avec des truands, habiter quelque part sans donner dans l’oeil… Une chambre dans laquelle il fait chaud même en hiver. Peut-être de temps en temps au cinéma. Un petit emploi de bureau sympathique. Il ne souhaite rien de mieux que ça. Amen » (p. 36).

Willi aimerait tout simplement « être comme les autres » (p. 41) , mais les autres – encore une anticipation – sont ceux qui ne se soucieront guère de ce qu’il adviendra de lui, qui lui mettront des bâtons dans les roues, qui le traiteront comme un chien. Mais en quoi Willi Kufalt est-il « autre » et qui est-il au juste ? Répondre à cette question signifierait se remémorer un temps perdu, un « avant » mythique dont le souvenir a été effacé par la prison :

« Il s’efforce d’y voir clair. Toutes ces mesquineries rendent la vie difficile, avant tout était plus facile, lorsque j’étais dans ma cellule, sans penser à rien. Je dois veiller à ce que tout devienne plus facile. Autrement je n’y arriverai pas, je suis trop faible… Tout devient tout de suite insupportable. Il faudrait un commencement en douceur, quel qu’il soit… » (p. 59-60).

Après la nuit, il y a le jour ; après la noirceur, la lumière. Willi ne sait plus. Il rêve d’un temps où « tout était plus facile ».Mais de quel temps s’agit-il ? Avant, c’est quand ? Une autre question sans réponse, qui nous livre toutefois quelques éléments de son identité. Il est faible, dit-il, faible dans la mesure où « tout est trop trop vite », ce qui renvoie l’image d’une personnalité figée dans le court terme, impatiente, sans les moyens adéquats pour faire face aux difficultés de la vie quotidienne. Dans ces propos, il y a un passage continuel entre la responsabilité individuelle (« Je dois veiller… ») et des attentes dont le sujet est indéterminé (« On devrait… »), entre le présent et le conditionnel. Il sait ce qu’il devrait faire, il sait aussi qu’il n’en est pas capable, une incapacité qui justifie l’inaction.

Les entretiens avec un gardien et le directeur et le pasteur ne sont pas faits pour le rassurer. L’un rappelle à Willi les cinq millions de chômeurs qui font la queue pour trouver un travail tant soit peu convenable. L’autre essaie de le ramener à la réalité en le comparant à un malade qui quitte l’hôpital :

« C’est maintenant que commencent les difficultés. Vous êtes comme un malade, qui a gardé le lit longtemps. Vous devez réapprendre à marcher »

À quoi Willy répond :

« Je serais presque tenté de vous prier de me garder ici… Je suis un homme auquel on vient de couper les mains » (p. 72).

Le scénario est posé. Willi Kufalt, malade ou handicapé, a besoin d’une période de convalescence que la société, elle-même en crise, n’est pas prête à lui accorder. Et les embûches font leur apparition dès les procédures de sortie. Le directeur lui propose de travailler dans un atelier protégé, offre que Willi refuse dans un premier temps, parce qu’on ne lui donne pas le temps d’en lire le règlement. Il a besoin d’un certificat de départ (« Abmeldung ») et on lui en fournit un avec le sceau du pénitencier. Au lieu de lui donner l’argent qu’il a gagné pendant son séjour en prison, celui-ci va être versé sur un compte contrôlé par le service de patronage qui le lui versera au compte-goutte. Et le voilà dehors…

C’est ça la liberté ?

La première étape, une fois sorti de prison, c’est une maison de transition à Hambourg, qui offre logis et un travail consistant à taper des adresses à la machine pour l’envoi de dépliants publicitaires. Willi n’est pas dupe, ce n’est pas encore la vraie vie, juste un prolongement de la prison. Il s’est trompé de liberté. Un accueil on ne peut plus froid, des règlements absurdes et vexatoires, un travail harassant et mal payé : ce n’est pas vraiment un changement de décor :

« Au moins il n’y a pas de barreaux aux fenêtres. À part ça, c’est la taule… » (p. 122).

Mais y a-t-il une liberté ailleurs ? Est-elle accessible à quelqu’un qui, comme lui, en a été privé pendant cinq ans ? Willi commence à en douter, et le sentiment d’exclusion s’accentue. Il est dehors et se sent en dehors :

« Est-ce la liberté qu’il a attendue pendant cinq ans ? Oh, mon Dieu, la liberté ! Faire ou ne pas faire ce qu’il veut… » (p. 162)

Mais Willi Kufalt ne veut pas décrocher la lune, ses ambitions de liberté ne vont pas au-delà de son souhait de mener une vie « comme les autres » : un boulot pas trop mal rémunéré, une chambre et de quoi se payer une bière de temps en temps. Des besoins modestes certes, mais difficiles à réaliser à court terme dans une Allemagne secouée par la crise économique et les conflits sociaux. Et c’est là que le bât blesse, car Willi demande peu, mais tout de suite, supportant mal que le temps s’interpose entre les besoins et leur satisfaction. Loin d’avoir intériorisé la notion chrétienne de sacrifice (souffrir maintenant pour jouir plus tard), il se heurte à tout délai comme à un obstacle insurmontable. Au centre de sa vision de la liberté se trouve cette idée qui est en quelque sorte le corollaire de ses ambitions : être « libéré » des soucis, des préoccupations de la vie quotidienne, des responsabilités. En d’autres mots : jouir, tout en étant dehors, de cette même « liberté » que lui offrait l’enfermement. C’et dans ce sens qu’il faut interpréter les propos de Willi lorsqu’il se dit hanté par la prison :

« Est-ce que dans le cerveau y a-t-il de la place pour une cellule, pour un espace restreint équipé de barreaux et de cadenas, et pour quelque chose sans forme qui déambule d’un coin à l’autre, quelque chose d’enfermé qui ne sortira jamais ? » (p. 205)

La vie „comme les autres“, si souhaitable soit-elle, ne libère pas des soucis. Seule la prison donne accès à ce type de liberté. À moins de s’engager sur la voie des « malins » (Schlaue) qui savent profiter des opportunités – légales ou illégales, peu importe – lorsqu’elles se présentent. Willi Kufalt est constamment tiraillé entre ces deux pôles, avec le mirage de la prison en toile de fond : il trouve un semblant de normalité, trébuche sur un obstacle, rêve du grand « coup » et se laisse entraîner dans des affaires minables. Il se remet en selle, rêve de famille et d’enfants, tombe à nouveau dans un piège et les truands ne sont jamais très loin.

Bien entendu, la société ne lui fait pas de cadeaux, comme elle n’en fait pas à tous ceux qui, sans travail, vivent en s’arrangeant comme ils peuvent. Willi a une chambre douillette, peut continuer à travailler dans l’atelier de la maison de transition, a même rencontré une fille qui partage ses soirées. Une petite vie, comme il l’imaginait, mais les fins de mois sont difficiles, les problèmes s’installent. Et s’il se mettait à son compte, avec les collègues de l’atelier, tous des repris de justice ? Une opportunité se présente, Willi fonce la tête baissée et se retrouve en prison, accusé d’avoir acheté des machines à écrire frauduleusement :

« Cent deux jours et de nouveau dedans ! Parfait. Pourquoi trimer ? On aimerait se cogner la tête contre un mur, se pendre… Les soucis que j’ai eus pendant ces trois mois, ce n’est pas possible… » (p. 297-98).

Liberté rime avec soucis : cette équation ne se dément pas. Et la nostalgie de la prison, de sa prison, refait surface :

„Je veux retourner en prison. Tout ça ne sert à rien, je m’en rends compte, autant y retourner... Moi, ça ne me fait rien, ça m’est égal... Laissez-moi retourner dans ma cellule. C’est la malchance qui me colle à la peau “ (p. 302).

„Après la déconfiture des dernières semaines, le souvenir de la prison a émergé de la mer grisâtre de sa vie comme une île de bonheur. N’était-ce pas une vie merveilleusement tranquille dans sa cellule, lorsqu’il n’était question ni d’argent,ni d’endroit où loger, ni de travail, ni de faim ?“ (p. 310).

Mais la prison, pour cette fois, ne veut pas de lui. Vite relâché, Willi remet l’ouvrage sur le métier. Une nouvelle tentative de gagner honnêtement sa vie en tapant des adresses s’enlise assez rapidement, faute de clients et aussi à cause de la lassitude qui l’envahit peu à peu. Un cercle vicieux, fait d’échecs, de découragement et d’alcool, s’installe dans sa vie, mettant en place les éléments qui vont conduire Willi vers la prochaine catastrophe.

Le chemin de croix

Willi est libre, mais la liberté se refuse à lui. Il est libre, mais sans un sou et sans la force de réagir. Il est libre de se réfugier dans une chambre qui, contrairement à sa cellule, ressemble plutôt à un trou sombre et malodorant. Figé dans sa déchéance, il est incapable de prendre la moindre décision. Continuer sur la bonne voie ou chercher des opportunités en dehors de la légalité ? Même le glissement vers la mauvaise pente se fait malgré lui, au hasard d’une rencontre avec un ancien camarade de pénitencier. Il suffit de quelques cigarettes et de la vue d’un portefeuille bien fourni, pour que Willi tombe dans le piège. Les billets de banque, que son camarade lui refile, sont des faux, et c’est Willi qui les « recycle » sans le savoir. En ce moment il n’a plus le choix, il est à la merci du truand et doit marcher dans la combine que celui-ci lui propose, un vol à la tire.

Plus spectateur que complice, il regarde les évènements se dérouler devant lui comme s’il ne faisait pas vraiment partie de la scène. Ce type de délinquance, qui pose plus de problèmes qu’il en résout, n’est pas pour lui. Une vie normale ou une vie de truand : des soucis d’un côté et de l’autre de la barrière, des contextes de vie interchangeables. En prenant conscience qu’il ne sera jamais un véritable malfaiteur, l’image de la prison refait surface, ou plutôt l’image d’une existence ordinaire qui mime celle de l’enfermement :

« Soudain Kufalt se rappela de ce qu’il voulait vraiment : ce n’était pas une carrière de truand dont il rêvait, mais le début d’une petite vie tranquille et honnête » (p. 326).

C’est avec un tel sentiment que Willi, une fois empochée sa part du butin, quitte Hambourg et se rend dans une petite ville, la même petite ville où il a vécu pendant cinq ans derrière les barreaux, tentative on ne peut plus naïve de concilier prison et liberté et de retrouver dans un retour vers le passé la chaleur d’un chez soi, si précaire soit-il :

« Il est en quelque sorte un prisonnier qui revient de son propre gré sur les lieux de son emprisonnement… Nous rentrons tous à la maison, chez nous. Toujours. Rien n’est plus idiot que le bavardage sur la nouvelle vie que nous pourrions commencer… Tout est là, une vie ratée, sans perspectives, sans courage, sans patience » (p. 329-330).

Retour à la case de départ ou presque : une autre étape sur un chemin de croix, dont on connaît le dénouement, en alternance avec des courtes périodes de répit. Il y a tout d’abord la recherche de travail, les refus, les préjugés, ensuite un semblant d’intégration. Willi reprend goût à la vie, rencontre des amis, trouve du travail, il est même question de mariage. L’avenir reprend un sens, les éléments d’une nouvelle vie, fragile, se mettent en place. Un équilibre instable, certes, un « soupçon de bonheur » (p. 362) dans une petite vie qui lui fait presque oublier la prison :

« Délit, tribunal, prison, disparaissent de son esprit : la vie normale recommence là où elle s’est arrêtée » (p. 395).

Peine perdue, la prochaine catastrophe est au rendez-vous. Accusé injustement d’avoir volé de l’argent à une de ses clientes, il est arrêté et mis en détention préventive. Willy sort de prison, après que la police ait arrête le vrai coupable, mais il en a assez. Il a fait un effort, ça n’a pas marché :

« Il n’a plus envie de faire des efforts, de toute façon ça va mal tourner… Rien de bon pendant ces neuf mois, pas une seule heure. Il s’est donné de la peine pour rien » (p. 457/ p. 474).

La logique de la récidive, telle qu’elle se présente dans le récit de Fallada, est implacable. Tout semble pousser Willi Kufalt, un anti-héros, vers la délinquance et le retour en prison : son statut d’ex-détenu, les préjugés, les vexations, les problèmes de la vie quotidienne. Mais il y a autre chose. S’il est vrai que Willi est poussé vers la récidive par des forces qui échappent à son contrôle, il est tout aussi vrai qu’il se laisse pousser. La résistance qu’il oppose, la peine qu’il se donne pour sortir du cercle vicieux, ne font pas le poids, ceci d’autant plus que ce à quoi il aspire – une vie « normale », sans soucis ni problèmes – n’existe pas. Contrairement à ce que pense Willi, « être en liberté » n’est pas synonyme d’« être libre ».[vii] S’il est assez lucide pour reconnaître sa part de responsabilité, Willi ne semble pas disposer des moyens pour agir autrement :

« Il n’était pas capable de suivre une voie sans embûches, il se posait lui-même des pièges … et brisait tout sur son passage, même si ce n’était pas nécessaire » (p. 474).

La chute

À partir de ce constat, il n’y a qu’un pas à franchir. Au lieu de continuer à se battre, il se laisse entraîner par le courant. Si le fait d’avoir été en prison représente un handicap insurmontable, alors à quoi bon lutter contre ? Si la prison est de toute façon au bout du chemin, autant faire quelque chose qui en vaille la peine. Il retourne à Hambourg et vit tout d’abord de l’argent qu’il a mis de côté, sans très bien savoir de quoi sera fait son avenir. Willi n’est pas un criminel, mais le fait est qu’il est respecté seulement par les personnes qui voient en lui un véritable criminel. Alors, il va satisfaire leurs attentes. Dès ce moment, une seule idée dans sa tête : réussir un coup fumant, lui permettant de mener une belle vie par la suite. Il change de nom, va à la recherche d’une opportunité, il trouve une bijouterie qui ferait l’affaire, contacte un ancien camarade de prison. Mais celui-ci n’est pas dupe. Il sait que Willy n’osera jamais passer à l’acte et lui attribue un rôle secondaire. Et Willy hésite, il ne sait plus très bien où il en est, cherche refuge dans l’alcool. Des problèmes partout, il ne sait faire rien d’autre que de déambuler dans sa chambre, comme il le faisait dans sa cellule. La seule différence : huit pas, au lieu de cinq. En attendant le moment propice pour passer à l’acte et montrer aux autres qu’il est un vrai truand, il se promène en ville, sans un but déterminé, en faisant les comptes de ce qui lui reste dans la poche et en anticipant la fin de l’histoire :

„Tout lui était désormais égal, tout était gris, terne, désolant. C’était la fin“ (p. 501).

Le reste, c’est du remplissage. La chute de Willi se passe d’après un scénario que d’autres ont écrit. Tout ce qu’il fait n’a qu’un seul but : le retour en prison. Les actes qu’il pose, les transgressions qu’il commet apparaissent comme une ultime tentative désespérée de se trouver une identité autre que celle d’ex-détenu, de s’affirmer dans un monde qui lui échappe. Au cours d’une de ses promenades nocturnes, Willy croise une fille, la suit, lui assène un coup de poing au visage et lui arrache le sac à main. Sept Mark et quelques centimes. Willy se sent mieux :

« Il avait enfin réussi à faire quelque chose et cette nuit, il dormit tranquille. Un pauvre sac, ce premier sac. Mais le sac et son contenu n’avaient aucune importance pour lui. Ce qui comptait, c’était le regard apeuré, la fille qui s’enfuit, les cris de douleur. Il n’était plus en ce moment le dernier des derniers, celui qu’on piétine : il était désormais capable de piétiner et de faire souffrir les autres » (p. 503).

Après ce premier acte de violence, d’autres vont suivre. Willy Kufalt ne se contrôle plus. Il attend tout simplement que tout soit fini, ses actes – naïfs, empruntés, inconscients – ne sont que prélude à un dénouement inévitable : il ne prend pas la peine de se déguiser, accomplit ses méfaits au même endroit, collectionne les sacs volés dans sa chambre. Lorsqu’il apprend que son camarade à fait le coup de la bijouterie sans lui, il le dénonce à la police et essaie ensuite – maladroitement – de lui soutirer une partie du butin. Enfin, il ne trouve rien de mieux à faire que de voler sa logeuse, avant de se faire cueillir par la police les mains dans le sac. Willi n’est pas surpris, il a joué le rôle qu’on attendait de lui, il a satisfait les attentes :

« Tout était juste. Tout s’imbriquait à la perfection pendant les dernières semaines, pendant lesquelles il était descendu peu à peu au fond du gouffre, en se cachant les yeux devant un dénouement inévitable » (p. 541).

Condamné à sept ans de prison, Willy Kufalt retrouve enfin sa cellule, son « chez soi » :

« En fait c’est ce qu’il y a de mieux que d’être de nouveau en prison. Ici, tout est à sa place... Kufalt est à sa place, Kufalt est content. On lui a donné une belle cellule... Ici, c’est mieux que dehors... C’est bien d’être de nouveau chez soi » (p. 566-571).

Dans sa banalité, l’histoire que Fallada nous raconte, constitue sous certains aspects un paradigme qui légitime tout un discours critique à la fois envers la prison et envers la société, considérées comme les principaux facteurs de la reproduction de la délinquance. La privation de la liberté, quel que soit son contenu, ne remplit pas les fonctions que le législateur lui attribue, au contraire, elle déploie des effets pervers. La société, quant à elle, ne cesse de semer des embûches sur le parcours qui devrait amener les ex-détenus vers leur réintégration. Selon ce paradigme, la société alimente la prison à deux niveaux : en tant que responsable de la délinquance et comme moteur de la stigmatisation et de l’exclusion. Mais l’intérêt de l’œuvre de Fallada doit être recherché en aval de ce qu’est devenu entre-temps un stéréotype. L’histoire de Willi Kufalt ne saurait se réduire à une illustration d’un processus irréversible, dans lequel l’individu n’aurait aucun rôle à jouer. Malgré son titre (« Qui a déjà mangé de la gamelle… »), le roman de Fallada est une œuvre ouverte, nous donnant accès à tout moment aux chemins alternatifs – si précaires soient-ils – que Willi Kufalt pourrait emprunter. Il n’y a aucune nécessité aux gestes que pose le protagoniste du roman, la logique qui les informe relève à la fois du hasard et de l’indolence de Willi, toujours prêt à se laisser transporter par le courant plutôt que de lutter contre.

[Lire la suite sur : http://infoprisons.ch/bulletin_7/ecrivains_fallada-doeblin.pdf ]

Claudio Besozzi, juillet 2012

[i]Source Infoprisons : PLATEFORME D’ECHANGES SUR LA PRISON ET LA SANCTION PENALE, Bulletin électronique No 7 / novembre2012, Adresse email : bulletin@infoprisons.ch, ce bulletin est aussi disponible sur notre site : http ://infoprisons.ch

[ii]Hans Fallada, Wer einmal aus dem Blechnapf frisst, Berlin, Aufbau-Verlag, 7. Aufl., 2009, p. 546-558.

[v]Son journal, publié sous le titre de „In meinem fremden Land“, représente une tentative plus ou moins réussie, de justifier sa décision. Voici ce qu’il écrit à ce propos : „Und da sitzen Narren draussen im Auslande, sie sitzen recht bequem und gefahrlos und die beschimpfen uns als Konjunkturritter, als Söldlinge der Nazis – sie tadeln unsere Schwäche, unsere Tatenlosigkeit, unser Mangel an Widerstandskraft. Aber wir haben es ertragen und sie nicht, und wir haben uns jeden Tag gefürchtet, aber sie nicht...“ (Hans Fallada, In meinem fremden Lande, Berlin, Aufbau-Verlag, 2009). Sur la position ambigüe de l’écrivain face au national-socialisme, voir la postface de Jenny Williams et Sabine Lange dans l’œuvre citée (p. 271-286), ainsi que le commentaire de Geoff Wilkes dans „Ogni uomo muore solo“, Palermo, Sellerio, 2010, p. 717-740.

16:46 Publié dans Bibliographie, Recensions, Textes sur Hans Fallada | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0)