10/09/2016

The Nightmare

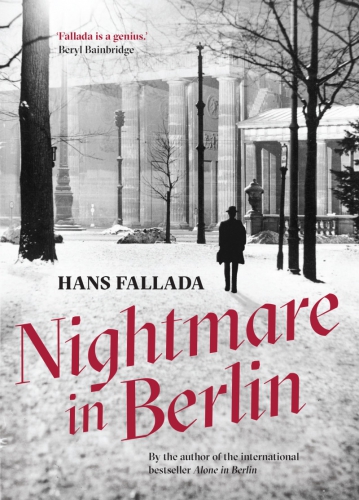

Hans Fallada novel, Nightmare in Berlin, gets first English translation

Story of married couple contending with a devastated postwar Berlin follows runaway success of Alone in Berlin

Thursday 28 July 2016 15.23 BSTLast modified on Tuesday 2 August 201612.54 BST

Hans Fallada’s 1947 novel Alone in Berlin was the hit book of the summer six years ago, selling 300,000 copies and making a bestseller of an author who had been largely forgotten. Now the late German author’s Nightmare in Berlin, an autobiographical novel beginning on the day the war ends, is to be published in English for the first time.

Released in German as Der Alpdruck (“The Nightmare”) in 1947, the year of Fallada’s death, the novel is the only book other than Alone in Berlin to have been written by the author in the post-war period. It tells of a man, Dr Doll, and his wife, who are taking shelter in the German countryside, haunted by nightmarish images at night, when the Russians invade. They return to Berlin after the end of the war, and attempt to resume their lives, but confronting the reality of life in the devastated city, they fall into morphine addiction, with each dose a “small death”.

“More than anything, [Dr Doll] wishes to vanquish the demon of collective guilt, but he is unable to right any wrongs,” said the novel’s English-language publisher Scribe UK, which will publish the book in the UK in October. “As the German nation tries to awaken from the nightmare that Hitler’s state had descended into, Fallada’s protagonists slowly wrestle their way out of their own oblivion, eventually finding a way forward.”

Scribe said the novel was “heavily autobiographical”, with the author’s “turbulent life … a mirror for the imploding society he documented”. Fallada’s biographer Jenny Williams writes in her biography of the author, More Lives Than One, that Der Alpdruck “draws on his experiences from April 1945 to July 1946”, and notes that the author himself called it “half fact, half fiction”. In Fallada’s preface, she adds, he describes the book as a “report, as true to the facts as possible, of how Germans felt, suffered and acted from April 1945 into the summer of 1946”.

Williams calls Der Alpdruck “the book that cleared the way for Alone in Berlin”. Fallada, the pen name of the German author Rudolf Ditzen, rose to fame with the publication of the 1932 novel, Kleiner Mann - Was Nun? (“Little Man – What Now?”), but was addicted to morphine and spent his life in and out of psychiatric hospitals and prisons.

Ditzen chose to stay in Germany when the Nazis came to power, and was put under pressure to write antisemitic works. He completed Der Alpdruck in August 1946, the year before his death. “It’s patently autobiographical,” said translator Allan Blunden. “He and his wife were both drug-addicted, and that figures largely.”

Fallada would go on to write one more book, Alone in Berlin – in German published as Jeder Stirbt Für Sich Allein (“Each dies only for himself”) – in 1947, but, like Der Alpdruck, the book was not published until after his death that same year.

Inspired by a true story, Alone in Berlin is set in Berlin in 1940 and follows the story of the couple Otto and Anna Quangel, who begin a campaign of resistance against the Nazi regime when their son is killed in France. It topped charts in the US and the UK when it was translated by Michael Hofmann and published for the first time in English in 2009, selling 300,000 copies in the UK, an extraordinary amount for a translated classic. A film adaptation starring Emma Thompson and Brendan Gleeson is due out next spring.

Although other works by Fallada have been published in English – including The Drinker, A Small Circus and Wolf Among Wolves – this October marks the first English-language release for Der Alpdruck.

“The moment I saw a sample translation, I was so impressed with it,” said publisher Henry Rosenbloom. “It’s one of only two postwar novels, along with Alone in Berlin. He was writing them around the same time, and in terms of his psyche, and what was happening in Germany at the time, they are closely related. It’s very compelling, very gripping. The thing about Fallada is that he’s got his extraordinary intensity when he writes. Every line is supercharged with vividness, and that’s especially the case with this novel, which is set in a very harrowing time in Germany, in Berlin immediately after the war. It’s a nightmare.”

Williams writes in her biography that the novel contains inconsistencies, which she believes are “due largely to Ditzen’s inability to resolve the conflicts arising from his recent and current situation. Thus Doll, Ditzen’s protagonist and alter ego, feels at the same time both detached from and implicated in the fate of the German nation.”

It “comes to life”, she writes, when the author describes “places with which he is familiar, like the sanatorium where Doll goes to be cured of his morphine addiction.”

“The novel ends on a positive note, with Doll’s discharge from hospital and his optimism that ‘the nations will get their houses in order again, even Germany, this beloved, this wretched Germany, this ailing heart of Europe will become well again’,” says Williams. But it is unlikely, she adds, “that Ditzen shared this optimism”.

15:38 Publié dans Actualité, Recensions, Textes sur Hans Fallada | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0)