22/09/2012

"writing is the essence of my life" (1/3)

HOW I BECAME A WRITER

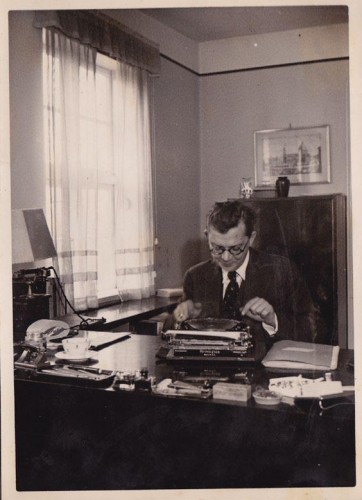

BY HANS FALLADA

Translator’s Introduction

During his life as a writer, Hans Fallada produced several short biographical sketches for publicity purposes, and he published some articles about particular experiences, such as his brush with the short-lived provincial putsch of 1923 which he fictionalized in Wolf Among Wolves in 1937. While living in Germany between 1933 and 1945, Fallada turned to autobiography as an uncontroversial genre, concentrating on his childhood in Our Home in Days Gone By (1941), and on his more recent life in the Mecklenburg countryside in Our Home Today (1943), and also publishing translations of Clarence Day’s Life with Father and Life with Mother in 1936 and 1938, respectively. But while he was sequestered in a psychiatric institution in 1944, Fallada secretly wrote a book-length account of his experiences in Nazi Germany which would have cost him his life if it had been discovered at the time, and which was not published until 2009, under the title In meinem fremden Land [In My Foreign Country].

“How I Became a Writer” was Fallada’s last venture into autobiography, and his most comprehensive in that it was completed at the very end of his life, and referred to most of the phases in that life. It was the final substantial production of the extraordinary twenty-one-month period between the end of the Second World War in April 1945 and Fallada’s death in February 1947 during which he wrote two novels (The Nightmare and Every Man Dies Alone) and numerous short stories, and also made several public speeches and radio broadcasts, struggling all the while with physical and psychological prostration, as well as with the deprivations of postwar Germany (mostly in a Berlin which he describes almost casually in “How I Became a Writer” as “very battered”).

However, to say that “How I Became a Writer” is Fallada’s most comprehensive autobiographical piece is not to say that it is completely accurate or frank. Some incorrect statements may simply reflect failures of memory, as when Fallada gives the publication dates of his first two novels as 1918 and 1919 rather than 1920 and 1923. But other statements are more than disingenuous, as when he says blandly that he “got sick” in his final year of high school, not that he was committed to a sanatorium after shooting his friend Hanns Dietrich von Necker.

Nevertheless, “How I Became a Writer” gives an essentially true picture of Fallada’s life. And his treatment of his profession demonstrates a striking honesty and humility. For the famous passage in which he says that his feelings while writing are “like intoxication, but [feelings] beyond all the kinds of intoxication caused by earthly means” takes the reader to the very center of Fallada’s psyche, and acknowledges by implication the episodes of substance abuse which punctuated his existence. And Fallada’s simultaneously—and I use the word deliberately—sober attitude to his profession is prominent both in his absorbing account of the mechanics of writing, editing, printing, and publishing his novels, and in his professional self-characterization. German generally applies three words to that profession: Dichter (which corresponds to “poet” in its broadest sense), Autor (“author”), and Schriftsteller (“writer”), and it is entirely typical of Fallada not only that he chooses the most modest of the three for the title of his last autobiographical piece, but also that on two occasions in that piece he describes himself even more unpretentiously as a Bücherschreiber (literally, “book-writer”).

Hans Fallada’s “How I Became a Writer” did not appear until 1967, twenty years after his death, in a collection of Fallada’s stories that was issued by his original publisher, Rowohlt. It is published here for the first time in English.

—Geoff Wilkes, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

oOo

HOW I BECAME A WRITER

Part one of three

BY HANS FALLADA

I want to tell you about how someone becomes a writer. But right away I have to pause. Because, I ask myself, does someone become a writer? Is it something you resolve upon, and work towards, always conscious of your goal, until effort, endurance, and luck bring you to that goal, so that from that point onwards you’re a writer?

I should say at the outset: I don’t believe that. I don’t believe that you become a writer, but that you are a writer, from the beginning of your life. It can take ages for you to realize it; I myself was thirty-seven years old when I wrote my first real novel. Until then I had generally been occupied with things far different from novels.

Because the way things turned out, I didn’t finish my high-school diploma, ever. I got sick in my final year, I was sent to the country, and when I was fit to walk and to learn again, I discovered that my knowledge of the higher mathematics, which had been quite patchy to start with, had now disappeared entirely, and my ancient Greek wasn’t much better. It would have taken years to catch up on what I’d lost, and those were the days in which everything had to happen at its appointed time, so that you completed your high-school diploma at eighteen or nineteen rather than twenty-two or -three; that was the only appropriate way. Anything else was inappropriate, and something as inappropriate as a belated high-school graduate could never, ever become a proper university student! That’s truly how it was in those days!

This meant that the family tradition had been broken; I, the oldest son, couldn’t become a lawyer, as had been customary in our family for some four or five generations. But what else could become of the boy? I can’t remember specifically who decided that I should be made a farmer. Farming was a long way from customary in our family. In my family you were a lawyer or a minister of religion, which meant that you were securely employed. And now I became a farmer: either because the doctors thought the country air would do me good; or because I happened to be living in the country at the time, surrounded by farms; or because my dear father didn’t know what else to do with me; or perhaps even because it was what I wanted.

A farmer, a gentleman who owned an agricultural estate, was readily available who was prepared to take me as a trainee if my parents paid liberally for my keep, which is how I found myself standing in a cowshed at three o’clock one morning, as boss of 120 cows and about a dozen milkers, and from that day onwards I was supposed to begin every morning of my life at three o’clock in a cowshed, seeing that the cows were milked properly, and that the milkers didn’t treat them roughly, and that there weren’t too many milk-hungry cats around—and I was so tired!

The day dragged on, and when the milk had been sent off to the early-morning train at last, I snatched a quick breakfast before I was dispatched to the fields, perhaps to the plowing or the day laborers working on the sugar beet or, if I was lucky, into the forest. Because then I could dawdle a little on my way to the forest workers, and I had to spend the rest of the day standing behind people driving them to work harder, because according to my boss, overseer Schoenekerl, the people were never working hard enough. And I wasn’t driving them hard enough.

When evening had come, when the horses had been fed, when I was so tired I could hardly stand, then the owner of the estate began his sessions with me. Standing bolt upright in his glossy riding boots, he started to discuss the operations of the farm, as he termed it, while I stood in my thin leggings, swaying gently back and forth, stupid with fatigue. I don’t know why the great man always prolonged these discussions so much. I saw the laborers who had fed the animals going home, later the foreman rattled his huge bunch of keys as he locked up the barns and the lofts, dusk began, the poultry girl chased the last birds into their coops, night fell, and the operations of the farm were still being discussed: The wheat needs saltpeter, the dung is distributed too unevenly in Field Seven, that has to be looked at again, and I also meant to say that I think the soil in that corner of the estate I mentioned has too much clay for sugar beet after all, what if we sowed wheat there again, with some alfalfa added…?

On and on, without end, day after day, year after year. Because even when I changed to different estates later on, the problems were always the same, I was always too easy on the workers, whatever turned out well had always been thought up by the owner, whatever turned out badly had always been messed up by me. The day was always too long, the pay was always too low. You have to admit, I was quite a long way from being a writer back then, and I can also assure you that I never spared a thought for books or anything like them. I was always tired, I was always hungry (because the estate owners’ wives tended to feed us employees rather sparingly), and I sighed at the prospect of writing even my obligatory letter home on Sundays.

But all this time—though I only realized it decades later—I was learning, learning in preparation for what I would eventually become: a writer. Because I was almost always among people, I stood behind the endless rows of chattering women who were hoeing the turnip fields, or digging out the potatoes, and I heard the women and the girls chattering, it went on from morning to night. And at night the estate owner rattled on, just as the laborers chattered in the barns and the stables. And there was no choice, I had to listen, I learned how they talk and what they talk about, what worries them, what their problems are. And as I was a very inferior member of the owner’s staff, who didn’t ride around on a horse, but at best might use one of the estate’s bicycles to save time, the laborers had no inhibitions about talking with me, so I learned back then how to talk comfortably with anyone. If you spend almost every hour for six months standing in fields of damn sugar beet, then you’re just one of the workers; it doesn’t matter how sheltered and uneventful your bourgeois upbringing was, you’ve become a kind of agricultural laborer now. And it doesn’t matter that you’ve been sent there by the owner to give orders, the workers know the score: He has to cuss at us, or he’s having a bad day, but he’s really no different from us. So you see, that’s what I harvested during my time as a farmer: It broke down my isolation, so that I became part of the common herd, with their worries, their joys, and their crises.

And really that was very good for me, because if I had followed my family’s usual path through a high-school diploma and the college thing and the legal stuff, I might never have become a writer, and that would have been a pity, because I still feel today that writing a novel is the most beautiful thing in the world, to sit down with the paper in front of you and to bring a world to life that wasn’t there before, not so that only I see it (we can all do that, when we dream), but so that my dreams become reality for others too. But more about that later.

Just now I’ll tell you a bit more about the isolation in which I had lived as a young man and from which my time as a farmer then liberated me. I had been a sickly boy, and an extremely moderate student, who often had to miss school for weeks and months because he was confined to his bed. Now, what do you do when you have to spend a long time in bed? You read! My good father believed in Jean Paul’s dictum that although books themselves aren’t good or bad, they probably make the reader better or worse, and because he believed in this dictum he kept a watchful eye on his bookcases and allocated my reading matter to me very carefully. But sick-days are long, and the books chosen by Papa were often boring, so I had to make shift for myself. From his earlier years, my father still retained a very wide selection of the little paper-covered volumes published by Reclam. His sense of propriety led him to sequester them in big cardboard boxes, which meant that he didn’t notice if any were missing, so I could use those boxes to satisfy my hunger for reading. My good father would probably have shuddered to see everything his good son was reading: Zola and Flaubert, Dumas and Scott, Sterne and Petöfi, Manzoni and Lie, all the literatures of the world jumbled up with each other, but without any kind of selection or censorship. I think I can say here that I don’t believe my indiscriminate reading did me any kind of harm: Such things as I didn’t understand slipped past me, and many things which I learned to value only later made no impression on me at all in my youth.

But the result was that I came to know the world of books before the world of reality, to know the fictional life of fictional characters before I had experienced anything of life. That’s the wrong way round, and if that had been all I did before becoming an author then I would have used only books as models to write more books, and would have known nothing about real life. There’s a poem by Gerhart Hauptmann of which I can only remember the lines “I am paper, you are paper, the world paper, the hand paper,” and that’s how it would have been with me if a chance happening which wasn’t a chance happening hadn’t put me on the turnip fields, hadn’t sent me out into life.

However, I have to say that back then on my sick-bed, while I was relentlessly devouring little Reclam volumes, I had no thought of writing such books myself one day. They held me spellbound, all those novels, because they gave my brain something to think about and my heart something to feel about, but back then they never awoke any kind of ambition in my breast to become a writer—I would have had absolutely no idea how to tell my father of such an ambition, and I imagine he would have been equally at a loss to know how I, or how anyone, could set about it, because after all there was no orderly career path you could follow, no degree you could do, no tests you could take.

In fact, there were tests, but you went through them out on the farm, in the endless fields of the big agricultural estates, living together with the laborers, with your colleagues, with the owners. Get yourself out into the open air, even get yourself sacked sometimes for complaining too much about the food, seek somewhat shamefaced refuge at home for a while, but then get out there again, a new job, new fields, new laborers, new colleagues and owners, and with them the old earth, the old work, the old chatter. Because people’s worries are the same everywhere, their happiness is the same, their faults are the same, their virtues are unmistakable.

That’s the life I led for several years, until the First World War interrupted it. No, I didn’t become a soldier—or only for eleven days, after which the army had seen enough of my military capabilities and sent me away again, for the duration of the First and of the Second World War. But the war took me to Berlin, to one of the wartime committees which existed then, the committee supervising potato-growing, and from then on my only occupation was to support the planting and increase the harvesting of potatoes in German territories. I became an expert in the potato industry, in my best days I not only knew around twelve hundred types of potatoes by name, but could also distinguish them from each other by their appearance, their eyes, their shape, and their color. It was still a life that had nothing to do with literature, a life spent on trains, spent traveling from one farm to another, building them up, giving advice, replacing old seed stock—and in between times I was in Berlin, in the city where I had gone to school, the only city where I feel I belong, even if I wasn’t born there and even if it’s very battered today. No, nothing to do with literature, and yet at the end of this period I wrote my first two novels. I can’t conceal my shame entirely, in 1918 and 1919 I wrote and published two novels, and indeed with the man who became my publisher many years later, my old friend Rowohlt. But I don’t acknowledge these first two children, later on I bought them up and had them pulped; I don’t want to know about them anymore, I shudder when I think back on them.

And why is that? Because they’re so bad? No, that’s not the reason; I wrote some weak books later as well, books that don’t give my any pleasure. But I don’t acknowledge the first two children because they weren’t my books, because I wrote them at the instigation, almost on the orders, of an ambitious woman, because they were pressed upon me, because I didn’t write them from my own internal motivation. That’s why I don’t count those two books, that’s why I don’t accept them, because they’re no children of mine. A real book has to grow inside you, it can’t be grafted onto you artificially from outside. Of course, almost everybody could write a book, but those aren’t the books that matter. You have to write books because you’ve got to write them! Those alone are the true books, and my first two novels weren’t that kind of book! They’re in the past—pulped and forgotten!

Then the inflation came, and unemployment, and drove me out of the big city again into the country, into my old occupation. But, alas, my old occupation was no longer what it had been, the people who had such jobs as existed were holding on tightly to them, I no longer had any choice, I had to take what I could get. So in those years I pursued a lot of professions to earn a few pfennigs here and a few marks there, and usually more pfennigs than marks. For a long time I patrolled the fields on a big estate, that is, I was a nightwatchman who spent my life chasing poor people who had cut the ears off the wheat or dug up the sugar beets to feed their goats with. I had to detain them, confiscate their meager pickings, and report them to the law, which then gave them a very small fine that, because of the continuing inflation, promptly became entirely meaningless. It was a strange occupation. Moving around night after night, over the endless fields of a huge agricultural estate in the depths of rural Prussia, mostly with a little colleague who became one of the most loyal friends I have had in my life, always on the alert, but still so often completely absorbed by the beauty of the night hours. I remember one time when we were lying at the edge of a forest, we had talked a little and were now gazing silently up at the stars, which were shining ever more powerfully and brightly, and I felt like I was lying in a cradle made of stars, and the stars were rocking me gently, and the whole world was rocking . . . And then I could see only the stars again, and they were growing ever bigger and brighter, and I was trying (as I hadn’t tried since I was a boy) to find my star, because very early in life I had chosen a particular star as my star, but I couldn’t pick it out among all that brilliance…

Then we were on our feet again and stumbled quite unexpectedly into a horde of mine-workers who were stealing wheat, about thirty of them, and we had left our rifles behind, and things looked bad for us until we bluffed our way out . . . Did I ever think of books back then? I think I barely even picked up a book for years and years.

I lost my taste for the profession of nightwatchman one morning later on, when one of my colleagues who had been beaten to a pulp crawled into the farmyard. He died a few hours later in our little office. I was through with that life, and became a kind of clerk to a master baker. But because of the inflation he had spurned that calling long ago and ventured among the wholesale potato merchants, and we loaded potatoes onto endless trains bound for Berlin, which made my master baker richer and richer, and his wife sadder and sadder, because really all he did now was sit around in the country inns, and I ran to the goods stations with the bills of lading and thought only of potatoes, just as I had thought only of potatoes for years before. I didn’t have much time for myself, the boss drank more and more, and I took more and more responsibility for running the business. Until the inflation came to an end and it turned out that my esteemed master baker and wholesale potato merchant was now not a rich man, but a very poor man. I don’t know if he managed to keep his bakery, I moved on and took a job on a big agricultural estate again, on the island of Rügen.

That’s where I lived for some years, and where things went well for me. My boss was a dyed-in-the-wool original, a real man, with a thousand eccentricities, and also the first boss I ever had who actually knew something about farming, and a thousand times more than I did. Because he knew by instinct what I, the one-time city boy, the judge’s son, had learned only laboriously, by trial and error, as something external to me. When he crossed a field, his foot and his whole body felt that the soil wasn’t loose enough, that it wasn’t ready yet, and he also knew instantly how to set about making it ready. I learned a great deal from this man, and most important he never expected me to shout at the laborers, because on his farm the laborers used their own judgment. He loved the soil, he loved what grew in it, and the workers loved it as he did, there was no need to shout at them.

He wasn’t a mild man, this boss on Rügen, oh no, he wasn’t that at all, and I’ll never forget what he did once with a milker who got angry and rushed at me with a pitchfork, how he tucked the man under one arm like a little child, carried him to the farmyard pump, in the middle of winter, and then held him under with just one arm while he worked the pump with the other, finally throwing the dripping man onto the dung-heap. No, he wasn’t a mild man, but he was a man of a thousand ideas, and I could tell stories about him for hours. Like when he insisted on learning to play tennis, but our attempts to transform good Rügen farmland into a solid tennis court failed again and again. Then he thought of the flat roof on one of the barns, and he had the longest ladder brought (naturally, because the barn was a good twelve meters high), and then we played tennis up there, not entirely without risk, oh no, by no means, if you hot-footed it after a ball and suddenly hit the brakes at the very edge of the roof and looked into the depths. Or he went sailing with me out into the Baltic Sea one beautiful October day in a little boat which he had made himself from sprucewood planks, and the wind and the waves (and my clumsiness) sent the mast overboard, and then the boat sank, and now we had to swim home again through the icy water . . . The high white chalk cliffs of Arkona shimmered ahead of us, we saw the sailors at the naval station moving around up there like little matchstick figures, but they didn’t see our heads among the waves, and so we had to swim, swim, swim . . . I got cramp after cramp from the cold water, and finally I reached the point where I declared that we would never get back to land, and I had had enough and would rather go under . . . But he didn’t accept that at all, swam up to me and said furiously that, for the Devil’s sake, I should stop making trouble for him, and he would keep clipping me over the ears until I swam on, so now I could make my choice! And, I’m standing here, so I suppose we did get to land, and not only that, we sailed out again quite a few times, in the same inadequate, unstable boat, which the sailors had fished out for us. Again, nothing to do with books, and I was about thirty years old by now…

But even the wonderful Rügen years came to an end, my eccentric boss had been somewhat eccentric in business matters too and lost his farm, and after various longer or shorter detours I found myself in Hamburg again. I was finished with farming, I didn’t want to play the boss’s representative anymore, I’d understood that I wasn’t cut out for it. I just didn’t like it anymore. I had a little rented room now, and I was what you might call a free man, if free man means that you’re completely free to eat or not to eat, to work or not to work. I didn’t have a boss anymore, I was finished with that too, I had become my own boss, and my job consisted in hiking from one export firm to another in Hamburg and inquiring if perhaps they had some letters to address, because I had bought myself an old typewriter and thought that I could earn my living with it. But there was lots of competition around, and not much exporting going on, and the best rate of pay I could get was four marks for a thousand addresses, or five marks for Spanish ones. It takes a long time to type a thousand addresses, which meant that during those Hamburg days, which were happy days nevertheless, I could only afford a hot meal once a week, on Sunday to be precise, and the rest of the time I could only afford half a liter of milk and two kippered herrings for lunch . . . Back then I thought that was a real poor man’s lunch, and the old lady I was renting from not only thought the same, but also told me so rather contemptuously on several occasions, but today I think that half a liter of milk and two kippered herrings for lunch is not so bad at all, not so bad at all…

My old Rügen boss had now also turned up in that same city of Hamburg, and was also living in a furnished room, on the limited funds he had salvaged from his former farm, which seemed to become more limited every day. But that hardly bothered him, because he had now turned his attention to the stars, and the world here below didn’t mean much to him anymore. He was making a thorough study of astrology, he had come suddenly to believe that you could read people’s fates in the stars, and whenever I visited him I found him sitting among endless tables and calculations and horoscopes, and when I spoke to him he seemed to emerge from another world…

(to be continued…)

08:21 Publié dans Textes de Hans Fallada | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0)